There are a few things you can’t do in a canoe. It’s unlikely you’ll ever land a marlin with a paddle in one hand, and mountain goat hunting from a canoe might be a stretch. For everything else, however, a good canoe

just may be the best friend you’ll ever have. Stable, sturdy, ready to haul you and your gear through plunging rapids, raging winds, and placid waters alike, a canoe will open up more doors to more places to fish, hunt, and camp than any other gear

item out there.

Who’s your buddy?

A good canoe.

Kagan McLeod

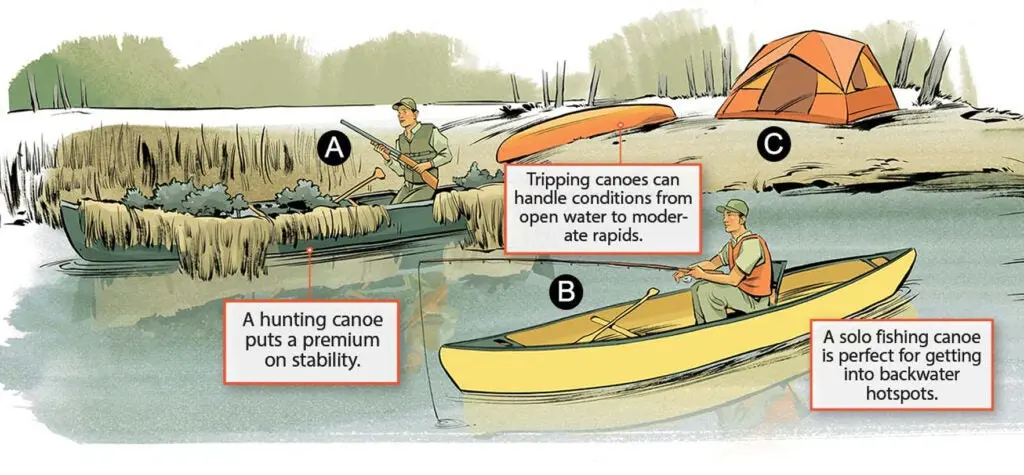

A. Hunting

For hunting, you need a wide, beamy canoe for stability. If you’re going to shoot from it, you don’t want it to tip. And if you bag something, you’ll need a solid boat to get your moose home—or to reach out and dip a squirrel from the water. If you’ll be duck hunting, a bit of tumblehome keeps paddles close to the boat and easier to hide. Slotted gunwales for brush and camo netting are handy, too.

B. Fishing

For quiet waters, beamy, rockerless boats are stable enough to cast from, and they swallow gear and a couple of kids with ease. For big-lake fishing with wind and waves, a deeper bow and pronounced bow flare will turn away windblown chop. If getting to big fish requires finessing whitewater, you’ll want a boat with rocker and a good Royalex layup. No matter the water, a bit of tumblehome makes it easier to land fish over the side. Find the right canoe »

C. Overnighting

Most tripping canoes are 17 feet or more and built to handle different conditions. Some perform better in certain waters than others. Asymmetric trippers cut through water and can be speedier than traditional designs over the long haul. Avoid too much tumblehome, which can make loading difficult, and which lets water over the sides. Big trippers with little to no rocker are flat-water boats, tracking true but relatively tough to turn. Other models give a nod to whitewater elements such as a bit of bow flare, to turn away waves, and a few inches of rocker, which makes it easier to turn and cast to fish holding tight against river boulders. Equip yourself with the best gear »

Kagan McLeod

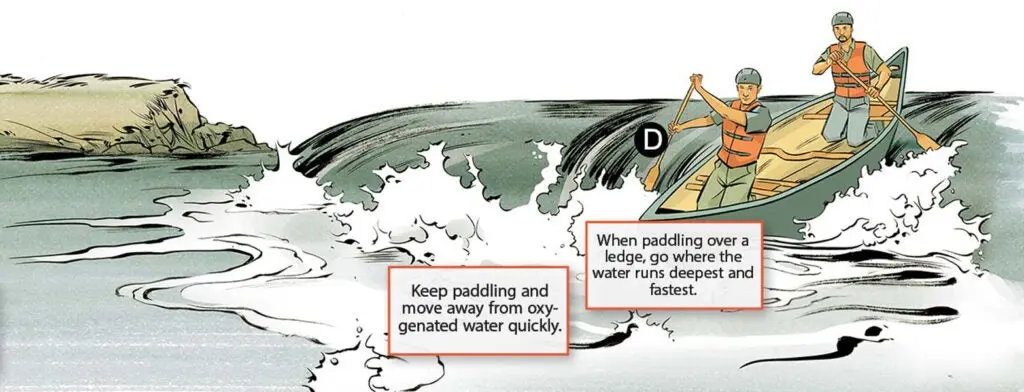

D. Fall With Grace

Negotiating a straightforward ledge drop is Whitewater 101…or 301, if the ledge is 5 feet tall and you’re paddling a boat that’s loaded with a ton of gear. Here are the basics.

Preparation: Cinch down your PFD and tie off any loose items in the canoe. Lower your center of gravity and improve your stability by kneeling in the boat. Fully communicate with your partner about the plan.

Entrance: If the ledge has a straight lip all the way across the river, line up where the water runs deepest and fastest over the drop. A downstream V is formed by water pouring between rocks or a gap in a cross-river ledge—that’s an ideal target, one you should go for if you can. Slow the boat with controlled back-paddling so you’re lined up perfectly with the gap you’re headed for.

Going over: Stay low and keep paddling; forward momentum is your best friend. As the bow plunges, be prepared to slap out a brace (stabilizing) stroke if one side of the canoe dips. Do this by putting your blade flat on the water and pushing downward. Do not grab the gunwales, as this can throw the canoe off balance.

Follow-through: Still upright? Don’t let up, because it’s not over yet. Keep your weight low and centered; any water that’s gotten into the boat can make it very tippy. Use strong, deep strokes to move away from the highly oxygenated—and less buoyant—water at the base of the ledge. Keep your head up and clear any other rocks or heavy current before high-fiving your paddle.

With a little thought, you can paddle solo, stand and cast, and carry a heavy load for long distances. Kagan McLeod

E. One-Man Motor

To track straight when paddling solo, put a draw, forward stroke, and pry stroke together to create a C-stroke. Reach forward and out from the gunwale with the canoe-paddle face at a 30- to 45-degree angle to the boat. Start the stroke by drawing the paddle toward you, sweep it straight to your hip, then finish with a pry away from the boat to straighten the canoe. Repeat.

A single paddler can handle a tandem canoe, but you have to turn the canoe around and paddle from the bow seat, facing the stern. This promotes stability. In rough conditions, kneel behind the center thwart to keep the bow in the water where it won’t catch as much wind. Scoot off-center toward your paddle side to shorten the boat’s waterline and give you more control.

F. How to Stand Up and Cast

Everyone knows that you should never stand in a canoe. With practice, however, you really can stand up and cast. Move as close as possible to the midpoint of the boat, where the hull is widest and most stable. If you cast with your right hand, stand with your left foot forward—this allows you to rock slightly forward and back to compensate for the casting motion. Bend your knees, brace the back of your calf against a seat or thwart for stability, and make no jerky movements.

G. Everything in Its Place

To pack for an overnight trip, keep the weight low and centered. Place items that you might need close by. Trim the boat by shifting weight until a double handful of water pools behind the center thwart. For a swift camping setup, pack one dry bag with tent, sleeping bags, and clothing, another with cooking gear and food. Once ashore, one paddler grabs the housekeeping bag and sets up the tent; the other gets a fire going and starts cooking. You meet in 20 minutes for appetizers.

![Field & Stream [dev]](https://images.ctfassets.net/fbkgl98xrr9f/1GnddAVcyeew2hQvUmrFpw/e4ca91baa53a1ecd66f76b1ef472932b/mob-logo.svg)