I’m sitting in a darkhouse, a fish hut with the door shut and the lone window almost completely blocked by a sheet of insulation. There’s just enough light in here to see whether I’ve got company. I do. I’m with Tim Zick, who was brought up just down the road in Osage, Minn. We’re focused on a rectangle in the ice, about 3 feet by 2 feet, from which an eerie light emerges. It’s like watching a flat-screen TV installed in the floor, except one recessed 27 inches—the thickness of the ice on Island Lake in early February. For the past three hours, we’ve been focused on the TV, which is showing the world’s slowest nature documentary—a live feed of the lake bottom, 8 feet away through the clear water. We stare as if we could summon a northern pike by sheer force of will. Zick works a carved wooden fish decoy tied to an old fly line. I hold a heavy iron spear, resting one of its tines on a ledge just above the water. When a northern shows up to investigate the decoy, I’m going to try to spear it.

The first European documentation of spearfishing dates to 1763, when a fur trader noted Ojibway anglers using decoys to attract lake trout under the ice in Michigan. But the practice is almost certainly far older than that. Indian Country, a project run by the Milwaukee Public Museum, describes the Ojibway practice as follows:

“The fisherman lay flat on his stomach and covered his head with a blanket. This blocked out the light and allowed him to see the fish as it came up to strike at the lure. The Indian, holding his lure at the end of a stick, jiggled it up and down to give it a swimming motion. In his other hand he held his spear ready to strike at the proper moment.”

There have been considerable upgrades in spearfishing accessories since then, with portable fish huts, power augers, and propane heaters making the game more comfortable. But the essence of it remains. It’s still a man in the dark with a decoy and a pointed stick, waiting—often for hours—for a fish to spear. In many ways, it’s the opposite of regular fishing. You’re not trying to get the fish to bite a hook; you’re trying to hook the fish yourself. The action doesn’t take place 20 yards away. It’s up close and personal. Eight feet, I’m told, is about as deep as you can throw a spear and connect. It’s fishing at its most primal, more like hunting than anything else.

Tim Zick surveys the ice on Island Lake.

Speaking My LanguageOutside, Jason Ulschmid is drilling holes in the ice with a power auger and placing tip-ups and tiny ice rods to catch walleyes and sunfish. Ulschmid is Zick’s buddy and an Island Lake expert. When he heard that Zick and I wanted to spearfish, he offered his hut for our use, over a shallow weed break where he knew pike liked to travel. After verifying that the spot was active via a tiny underwater camera, he marked where he wanted to put the 12-foot-by-7-foot hut, and drilled and tonged the ice for fishing holes. To make the rectangular spearing hole, he drilled six connected holes and then squared up the sides with an ice saw—a pole with a wicked-looking, folding blue blade, 3 feet long with oversize teeth. The hut is its own trailer. He hitched it to his truck, winched it up until the wheels were clear, backed it into place, and then winched it down again. Once it was in position, he and some buddies banked it, shoveling snow up around the sides to block the wind. This added a bit of insulation and kept the holes from freezing over as quickly.

I told Ulschmid how comfortable and functional his hut was and asked what one like it cost. “I have no idea,” he said. “I made it.” Turns out he’s a tool and die maker. Which means, as Zick put it, “If you can think it up, Jason can probably make it.”

Zick’s uncle Keith comes by the hut and catches three sunnies in 45 minutes. He is in between bouts of chemo for bone cancer and takes naps so he’ll have the energy to come to the darkhouse. Like everyone else I’ve talked with here, he has been ice fishing for as long as he can remember. Ulschmid started at 6 months old. “My dad would get one of my uncles to warm the fish house before we left. Then Dad would wrap me up and take me out onto the ice.”

From left: A box of decoys; Ulschmid drills a new hole.

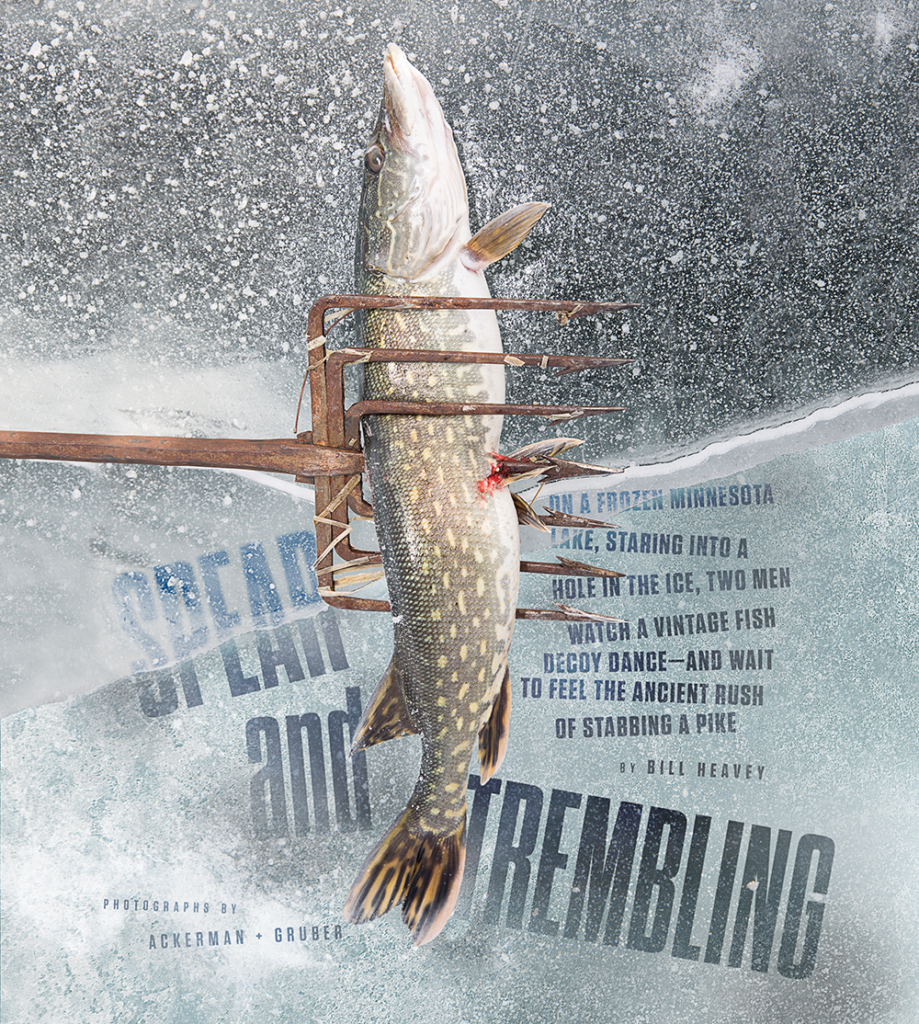

Back in the hut, Zick and I scarcely turn our heads to greet whoever comes or goes. We’re focused on the hole. The spear in my hand is iron, 5 feet long, and maybe 15 pounds, with a clothesline tether tied to a ring at one end and seven barbed tines at the other. It’s anybody’s guess how old the thing is. Zick thinks that an uncle got it at a farm auction a good while back. Another uncle recently bid on a similar spear at an auction. He dropped out at $200 and didn’t follow the bidding after that, Zick says. A good spear is a prized thing in this part of the world.

Zick selected the fish decoy he’s using from about eight he keeps in an old lunch pail; the deke is 5 inches long and was carved 40 years ago by his grandfather, who fashioned the fins and tail from pounded-flat license plates. It was once painted red and white but now shows more wood than color. The strange thing is that the colors come back underwater. They’re vivid, almost like new. I have no idea why this is. When allowed to fall on a slack line, the decoy faithfully scribes four lazy counterclockwise circles before it comes to rest on the bottom. Zick works it hard for a full minute, making it dart and veer. Then he lets it sit a foot off the bottom. If I were a fish, I’d hit it.

There are many styles of jigging the lure, Zick explains, and he tends to jig harder and more frequently than most. “The movement is what attracts fish,” he says. “But they usually don’t come all the way until it’s not moving. Sometimes they’ll smash it first, then come back to finish it off. Sometimes they just kind of appear, like they’re curious. The rule of thumb is that they come in when you least expect it. And they always come from the wrong side.” He smiles and says what sounds like OOF-da.

He sees my look. “It’s something we say. It’s spelled u-f-f d-a. It’s kind of an all-purpose expression, for everything from surprise to exhaustion, relief to disappointment. And it’s better than cursing.”

In the HoleThe fish are surprisingly active beneath the ice. There’s water down there, so it has to be above 32 degrees, but it’s hard to imagine it’s more than a degree or two above that. And yet we’ve seen bluegills, perch, an eelpout, and a few northerns. If the bluegills are decent size, we pick up tiny ice-fishing rigs—20-inch rods and reels spooled with 6-pound line—and drop Flutter Bug jigs tipped with waxworms. Most of the northerns are in the 21⁄2- to 3-pound range. But there was one so big that I never saw the entire fish.

Zick had gone outside to confer with Ulschmid. I’d jigged the decoy but hadn’t touched it for five minutes. Then the curved, thick body appeared in a corner of the TV. I realized it had been approaching the decoy and decided at the last moment to make a U-turn and skedaddle. I had just enough time to register its thick body curling away. It happened so fast that I was unsure whether I’d really seen it. Right now, there are fingerling perch that have emerged to hover just above the vegetation. This is not a good sign. They wouldn’t be out if there were a predator in the area.

Uff da.

So far today, I’ve thrown at and missed two fish. But misses are instructive. When you’re holding a spear and a fish appears, it rearranges your mental furniture. Primordial brain circuitry starts to hum. At the throw, the hum turns into a neurochemical roar. You have just crossed into previously unexplored territory of your brain. For me, the sensation carried with it the conviction that our species has been doing this for thousands of years, from whenever the first nomadic hunter-gatherers set up shop in cold places.

I’ve learned other things by missing. Though there are any number of ways to screw up the throw, a successful one depends on what I’ve come to think of as the Big Four. First, you have to get the tines into the water before the throw. Otherwise, the splash alerts the fish and it gets away. Second, the spear must be directly over the fish. You can throw at an angle, of course. You just shouldn’t expect to hit anything. This is mostly due to refraction, which I don’t understand. But I don’t need to. All I know is that when you’re looking at a fish from an angle, the fish is not where it appears to be. Third, the spear must be perpendicular to the surface. If you’ve canted it just a few degrees, the spear veers off course. (And the angle at which it embeds itself in the bottom advertises just how far off you were.) Finally, “throwing” the spear is a misnomer. “It’s more like dropping it,” Zick told me long before we even got on the ice. I assume that this is because it’s all but impossible to apply thrust evenly. In any case, once you’re in position, the throw is more like giving the spear the tiniest bit of encouragement. “It’s just your thumb and forefinger,” Zick said. “Like throwing a paper airplane.”

BlindsidedHours of concentration take their toll. I get hypnotized by the strange light and clear water. I reflexively cover my eyes each time somebody opens the door and lets in the blinding light of day. My back is so stiff I don’t even want to try getting up to stretch because I already know it’ll hurt. Every so often, the ice groans. Loudly. Sometimes it moves beneath our feet. Sometimes there are cracking sounds. I’m the only one freaked out by this.

“The ice contracts and expands,” Zick says, simply. “It’s O.K.” Right. If you hear a cataclysmic cracking that seems to indicate the ice beneath your feet will split like an old pair of pants and send you to a quick but rather chilly death, don’t be alarmed. I tell myself that there’s no need to get scared if Zick isn’t. It’s just part of the deal. I’m staying focused. The two misses have only whetted my desire to succeed. And I know that the classic spearfishing story is of seeing nothing for hours, then having the fish of your life show up suddenly and offer a two-second window just when you have decided to open a beverage.

I catch myself watching the motion of the decoy rather than the water around it. You want to be alert to any alteration of color or shape in the entire picture. That would indicate a fish before you recognize it as one. I rest my eyes periodically by letting them soften into wide-angle vision but remain alert for movement. I’m pretty sure my vertebrae are slowly fusing into this hunchbacked position and I’ll never stand straight again.

And then it happens. A northern materializes. It’s a carbon copy of the other 21⁄2-pounders that have cruised by today. But it’s nose-to-nose with the decoy, calm as can be. This one plays it by the book, appearing in the worst possible spot—the far corner, the one Zick’s chair straddles. Wordlessly we ready ourselves. I slip the spear’s tines 6 inches into the water and lean out as far as I’m able to get directly above the fish. I check to make sure the spear is perpendicular. Meanwhile, Zick gathers the slack in the decoy line toward him out of the spear’s path. “He’s mov—” Zick starts to whisper, but I’ve already seen this and sent the spear down with a paper-airplane flick. The telltale brown cloud billows. Only this time, at its center, something wriggles and thrashes. The tether comes alive in my hands. “All right!” Zick says. I lift the spear and the fish. I hit it dead center and about as far back on its body—3 inches in front of the tail—as anybody could and still come away with a fish.

“You got him at the last possible second!” shouts Zick. I did. I managed to cover all the Big Four rules and had some luck to boot. And I’ve been validated, initiated. It’s as if someone has just rolled a strike in the bowling alley of my brain. The missed opportunities and hours of waiting vanish like your breath in the cold. I step outside to show Ulschmid and am instantly snow-blind. I shield my eyes and wave the spear around, saying, “I finally got one!” I feel a clap on my shoulder and hear him congratulate me. As my sight returns, I see that the fish is so narrow that it could almost swim between the tines. I remark on this, but Ulschmid says, “What are you talking about? That just means less damaged fish. He’ll fry up great!”

Zick opens the door and emerges with a nice pike wriggling on the spear. It took me four hours to get one, and he has done it in the five minutes I’ve been celebrating. Zick is not the yelling kind, but there’s no hiding his triumphant smile. It’s a good fish, maybe 4 pounds. And he got it dead center right behind the head. “After you left, I got myself a pop and some crackers. Next time I looked down, he was nose-to-nose with the decoy.” He shrugs. Nobody knows when fish will show up or why, but eventually they do.

Missed ConnectionsThe next day, I manage to unlearn most of what I picked up the day before, botching uncounted throws before I connect with another pike, almost a clone of my first. It may not be the most productive way to fish, but the adrenaline rush is unsurpassed.

That night, we clean the fish at Ulschmid’s house, spreading newspaper over an island in the kitchen. Ulschmid shows me how to fillet along the Y-shaped backbone of a northern. The three of us are silent, intent on our work. I’m too absorbed in what I’m doing to watch the others, but I’m clearly the slowest. By the time I’ve done my third fish, Zick and Ulschmid are finished. We have about 8 pounds of boneless meat. Ulschmid fires up a pot of peanut oil, breads the fillets, and starts cranking out fried fish. Couples show up with potato salad, coleslaw, bread, and beer. I’m jealous. My flight leaves early in the morning. Meanwhile, the talk around the table is about who’s fishing tomorrow.

Uff da.

Photographs by Ackerman + Gruber. Typography by Eric Heintz

![Field & Stream [dev]](https://images.ctfassets.net/fbkgl98xrr9f/1GnddAVcyeew2hQvUmrFpw/e4ca91baa53a1ecd66f76b1ef472932b/mob-logo.svg)