The country stretches out wide in the sweep of early sun, the big Animus Mountains of purple and deep orange cliffs towering there like a fortress. The Chihuahuan Desert, at least this part of it, is misnamed: Here in the Boot Heel of New Mexico, it is a vast grassland savanna, high enough to catch the rains and snows, rich with black grama grasses and oak woodlands, cut with stone arroyos that roar with floodwaters and hold precious pools almost year-round—the watering holes of javelinas, black bears, toad muleys, and rugged little Coues deer.

This is the northern end of Mexico’s Sierra Madre, and the isolated mountain ranges—the Animus, the Peloncillos, the Big Hatchets—soar 8,500 feet and higher. We are here, in the bright days of early February, to chase quail with good dogs, to camp and eat and drink by the fire, to hunt and wander and see what adventures can be found on these great wild public lands, smack-dab on the border between the United States and Mexico.

New Mexico has plenty of beautiful public land for sportsmen to explore. Tom Fowlks

We drive old dirt roads south from the little community of Animus, stopping to glass a pair of Gould’s turkeys shaded up under a juniper and watch a Border Patrol truck negotiate a two-track along a faraway ridge. We eventually make a simple camp—a fire pit, a propane burner, a table for cooking, and some tents pitched on a flat spot with big Gambel oaks behind us and a few huge Ponderosa pines across the road. This isn’t what I think of as desert, but it is almost perfect Mearns quail country, and Rey Trejo, who brought us here, has been hunting it for more than 40 years.

Rey Trejo smiles with his English pointer, Gila. Tom Fowlks

Trejo has been a lot of things in his life. He made good money team-roping on the rodeo circuit but quit because he missed his wife and kids too much. He was a farrier after that, then a teacher, then the assistant superintendent of the Deming, New Mexico, school district. But through it all, he has been a hunter, and in New Mexico there is a lot to hunt: black bear, oryx, Barbary sheep, ibex, mule deer, pronghorn, elk, javelina, turkey, mountain grouse, Coues deer, mountain lion, coyote, and four species of quail. If there is anybody who spends more time afield, I don’t know them. Trejo seems tireless in his pursuits: He’s a past president of the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, his mules are always well-broke, his pointing dogs well-trained, his boots worn, and the bluing on his shotguns polished to silver. He has family on both sides of the border, and one of his grandmothers was a Yaqui Indian from the Mexican Sierra Madre. His ancestors homesteaded in New Mexico, on the Mimbres River, and one of his earliest memories is of roaming the canyons and riverbanks there and finding pieces of pottery left behind by the Mimbres people a thousand years ago. On the pottery are beautiful little portraits of the Mearns quail.

Daybreak on the borderland. Tom Fowlks

Of all of the game Trejo hunts, Coues deer and Mearns quail are the ones he loves the most. “My birthday is November 8, which was always the first day of New Mexico’s deer season,” he tells me. “My father started bringing me to deer camp when I was 8 years old. This high desert is where I started hunting, and where I come back to hunt the Coues deer and these Mearns, which I think may be the best gamebird there is. It holds for the dogs, it is incredibly beautiful, and it lives in only the best places.”

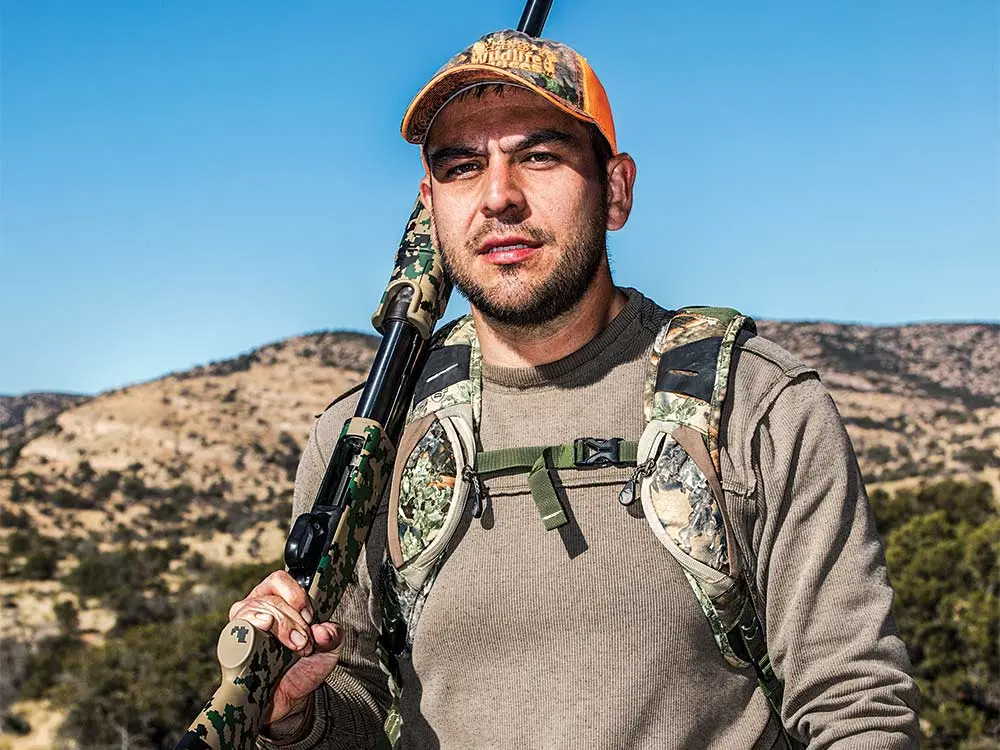

Gabe Vasquez Tom Fowlks

Trejo lets his English pointer, Gila, and a German shorthaired pointer, Rio, out of the dog boxes to stretch their legs just as Gabe Vasquez and Fernando Clemente pull up in a pickup truck. Vasquez is the local coordinator for the New Mexico Wildlife Federation, and at 33 years old is newly elected as the youngest member of the Las Cruces City Council. Clemente, Vasquez’s buddy, is a wildlife biologist working on big habitat restoration and wildlife recovery projects on both sides of the border. He comes by his trade almost as a birthright; although Clemente is an American citizen now, he was born in Mexico to a father who was a leading biologist for Mexico’s equivalent of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Rounding out our camp is Lew Carpenter, of the National Wildlife Federation, who joined us at midmorning and is down here to hunt and to learn about the wildlife on the border. As hunter-conservationists go, we have an all-star cast.

A German shorthaired pointer, takes a breather. Tom Fowlks

Hot and Cold

The dogs strike scent a couple of hours into the afternoon hunt, on a boulder-strewn hillside of bear grass, yucca, and some big gnarled oaks. I cross a dry wash and rush uphill, too excited, holding the little 20-gauge Ithaca over/under at the ready. Trejo hangs back to let Vasquez and me have the first chance at the flush. We move. Nothing happens. I kick a tussock of bear grass, and Vasquez stomps a pile of fallen oak branches. Either the Mearns are living up to their reputation for holding tight, or they are running somewhere ahead of us. I decide they’re running and take off, despite the fact that Rio is now backing Gila’s point.

There’s an explosive flush right at my feet, and the covey is suddenly everywhere in the air, flying in a sun-dappled cathedral space beneath the canopy of the oaks. I clear my mind, mount my gun slowly, and pick out a single bird on the left, frozen somewhere in an effective gap between conscious thought and instinct, and hit the bird solidly. The quail falls, leaving feathers drifting in the still air beneath the trees. I vaguely hear a couple of other shots from my friends, but I am lost, watching Gila retrieve my first-ever Mearns quail, then holding the male bird in my hand, marveling at the perfection of its blacks and mahoganies, the round dots, the little cinnamon headdress. Camouflage, yes, but beyond that, the pure and intricate artwork of creation. No wonder the Mimbres people were obsessed with these birds. Anyone who ever looks at one would feel the same.

We press on, unable to find single birds, despite a lot of walking. The hunting for Mearns is not about limits or a full frying pan. It is about dogs and friends, wild country, and a close study of the land. Trejo shows me what he calls “diggings,” a place where a covey of Mearns has cleared away the leaf litter and dug up the tubers of nut sedge or wood sorrel. “This doesn’t always mean they are close,” he says. “But at least you know there are some around.” We find lots more sign down the wash. Carpenter, Vasquez, and Clemente have peeled off and are headed uphill and back to the two-track road where we started; a few shots come from that way, and we learn later they got into a covey of scaled quail out in the open. As we hike behind the dogs, the light shifts, the temperature drops, and the Animus Range changes color yet again. “Let’s work our way back,” Trejo says. “I don’t like to hunt these birds and bust up the coveys too late in the day. They need to be able to gather up to survive the night, predators, the cold, whatever. Their lives are tough.” We didn’t know it yet, but our own lives were about to get a little tough that night as well.

Quad Squad: The wingshooters plan their hunt. Tom Fowlks

Back at camp, we build a roaring fire. We crack cold Modelo beers and begin prepping dinner. A paper plate of black bear sausage blunts the edge of our hunger. Trejo dices meat from an oryx that his son had killed with a bow and heats the discada, the traditional New Mexican cooking pan, named after the disk on farm equipment, on the propane burner. Homemade tortillas are wrapped in foil and set on a rock by the fire. When the tortillas are hot, the procession begins from the fire to the discada and back—burritos beyond imagining: oryx, bear, sweet onions, chiles, and garlic, a feast in every way born of this place and of the earth beneath our feet. A bottle of Cazadores (Spanish for “hunters”) tequila begins to make the rounds as we finish eating, and we toast the mighty agave. The talk gets louder, livelier, tales of hunting and misadventure and dogs. Clemente tells us about the jaguars that had been tracked here, venturing north from Mexico, and the ocelots and Mexican gray wolves, the most endangered wolf species on the planet. Overhead, the stars glitter fiercely. I live on the Rocky Mountain Front of Montana, one of the more isolated and unlit places in the country. But the darkness here in the Boot Heel is even more profound, more total, than that. There are almost no commercial flights overhead, no glow in the distance.

Standing so close to the fire, tequila heating my belly, I did not notice just how cold it is getting. When I go to the water jug, the twist-tap is frozen. I look over at the raucous group at the fire, the flames front-lighting them, another hunting story underway, and suddenly think, Man, I hope they brought good sleeping bags. Carpenter and I, who had come here traveling light, were about to learn a new lesson: New Mexican hunters who live just north of the border do not bring good sleeping bags. They might not even own them.

Vasquez empties a round at a wild quail. Tom Fowlks

Somewhere well before dawn, I crawl out of the tent clothed in everything I had brought and realize that the temperature has dropped to around 10 degrees. Carpenter, huddled inside, notes through chattering teeth that he has not slept yet. He shines a small flashlight through his sleeping bag. “See,” he says sadly, “the light goes right through. There’s not much there.” There are other stirrings in the camp, some of which may have been pleas for mercy from the unyielding frigidity of the night. At first light, Vasquez climbs into Clemente’s truck, starts it up, and slumps against the heater vents. The big blue water barrel is frozen hard as a stone, but we have all survived the night.

We walk above camp to find the line of sun as it crests the hill to the east and bathes the country in light and warmth. It does not take long to regain all that had been taken by the cold. Here in this deep southern reach of our nation, in this high desert, the sun is the real power broker.

The hunting party heads back to camp.

The hunting party heads back to camp. Tom Fowlks

Against the Wall

We take the quads past the country we’d hunted yesterday and explore some washes that Trejo and Clemente know about. There is water there, and the dogs strike scent right at the edge of the rocks—but then decide the scent is old and take off uphill, with all of us following. I am uncomfortable staying too close to the group; I want the freedom to swing on the birds and not have to worry about where everybody is, so I drift out to the flanks. This, I would learn, is the wrong move. Mearns flush hard, rise fast, then fall in a tumble, almost like snipe or woodcock. They don’t seek safety by flying wide or wild. When the shooting comes, Vasquez and Carpenter are in line with the rise. I never even see the birds. This plays out a couple more times as I stubbornly, and birdlessly, hold tight to my strategy. When I do get a shot at a bird, I miss, wanting it so badly that I doom my own reflexes. But I don’t let it ruin my day. We stop to rest at the crest of a long ridge; our now-unfrozen water bottles are passed around, the night and its tribulations revisited.

Directly to the south of us, just west of the Animus Range, is a wide plain, and somewhere in the middle of it, the border between the United States and Mexico. It is impossible for me to imagine a wall being built there, cutting this wild country in half, stranding the pronghorn, the Coues deer, all of the wildlife that lives by migrating from water source to feed and back again. How would the engineers get the wall through the Animus Range? How much would that cost? How would the water from the mountain snows and seasonal downpours get through the wall? There is nobody in sight and no evidence that illegal immigrants even use this stretch of the border. “The plans for the wall are the ideas of people that are far, far away from the reality of this place,” Trejo says. “It’s a solution that seems simple: People are coming in that you don’t want, bringing drugs or whatever; you build a wall and keep them out. But it’s not like that. This is not where the problem is. You can’t stop illegal immigration and drug smuggling by building a wall out here. But you can wreck this place. You can build roads and bulldoze and waste billions of dollars, but the wall here won’t be what stops the migrants or the smugglers.”

Warning signs and Border Patrol presence are common sights. Tom Fowlks

Vasquez, when he worked for Sen. Martin Heinrich, was a researcher on border security. “There are marijuana smugglers who use these isolated places to bring bales across, but most of the heroin and other drugs come in at the border cities,” he says. “In the past few years, they’ve been flying remote-controlled drones that deliver to wherever they choose.” That is another reason for the extraordinary level of Border Patrol presence, with the high-tech observation and listening equipment we’d seen mounted on trucks and trailers as we drove in. “The Border Patrol has all this new technology deployed, which has definitely had an impact here.”

I had noticed that we’d left the camping gear and a lot of other valuables totally unprotected back at camp. Although we have the shotguns, and Trejo and Clemente have handguns in their trucks, nobody has expressed any security concerns or even mentioned the sign we’d seen that warned of illegal immigrants and smugglers in the area. “People who don’t live here think there is all this danger out in the desert,” Vasquez says. “They imagine it to be like Tijuana or Juarez. That’s one reason they support the idea of a wall. They don’t know what is here—the camping, the wildlife, the mountains, all of this.” He sweeps his hand across the horizon.

The author pauses after a success shot on a wild quail. Tom Fowlks

Clemente, who spent a lot of time working to get his U.S. citizenship, has little sympathy for illegal immigrants of any nationality. His concern is for the wildlife that he has spent his life studying and hunting. “The wall would be a disaster for the wildlife,” he says. “Even for the quail and other birds that nest on the ground. For the deer and the jaguars, all of that, just a disaster.”

We all agree that illegal immigration has to be stopped, but that a wall here in this spectacular wilderness isn’t going to help. “The worst thing that could happen, and I could actually see this happening,” Trejo says, “is that the big contractors get all that money, come in here and start building the wall, and in a few years, when Americans realize that it was a bad idea, the project is abandoned, the money gone, this place changed forever.”

Left: A Gambel’s quail in hand.; Right: The gorgeous patterns on a Mearns quail make the bird a sought-after trophy for wingshooters. Tom Fowlks

The afternoon’s hunt is one of long trudging, in a corrugated country that trends toward the sky. Our party spreads way out, Trejo and I trying to keep up with Gila’s love of taking off, a pale streak through the mix of juniper and oaks, as tireless and focused as her master. I find some diggings, and then we locate birds, high up this time. I shoot poorly, while Trejo dumps two, decisively, that take some finding in the thick undergrowth, even with the dogs. Looking for the birds, I stumble on an immense pack rat’s nest, waist-high, dotted with javelina turds and snail shells—all the weird detritus that for some reason these strange rodents feel compelled to collect. The country has taken me over. I feel like I have begun something new. I could get better at shooting Mearns. It is a matter of getting used to how they rise and fly, how much time you have, how to control your mount and find, again, that gap between thought and instinct where the shotgun is a part of your body and your will. Finding the birds means an apprenticeship to landscape, of learning the details of their lives and figuring out where they are likely to be, and after that, to embrace the mystery and know that they could be almost anywhere. I am hunting in a place where jaguars sometimes stalk Coues deer, where there is so much public land that one could walk and hunt to the horizon, following the dogs, resting when exhaustion overcomes you, sleeping where night falls upon you. This is the gift. But the birds—dramatic, beautiful—are the key to that gift, the reason we are here, the grail that opens all the rest of the wonders of the wild borderland to the hunter.

Nobody can face another bitterly cold night in the sleeping bags that, we joke, have a comfort rating down to around 75 degrees. We pack up before twilight and head for Trejo’s house in Deming. The next day, we awake to another clear blue sky. Trejo hatches a plan to go for scaled quail on the public lands outside town. “There is a place I want to show you,” he says, “where I hunted coyotes from a windmill tower when I was in high school.” In 30 minutes, with Gila and Rio loaded up and whining in the boxes, we are gone again.

![Field & Stream [dev]](https://images.ctfassets.net/fbkgl98xrr9f/1GnddAVcyeew2hQvUmrFpw/e4ca91baa53a1ecd66f76b1ef472932b/mob-logo.svg)