Across much of North America, this is a golden age for big game hunters

. Thanks to private and government conservation programs, many species that were on the brink a century ago are now thriving, and others are on the way back. World records for pronghorn antelope and bighorn sheep were rewritten recently, and top marks for three of the four elk species recognized by Boone and Crockett have been reset since 2002.

“These are the good old days,” says Justin Spring, director of big game records for the Boone and Crockett Club. “We just got 12 top-10 entries across the categories in the last three years alone. That says there’s still potential for new records and conservation efforts are working.”

And yet a look at the Boone and Crockett book also shows that many top trophies are getting long in the tooth. For example, whitetail deer, which are arguably the greatest conservation success story and the most pursued big game animal in America, haven’t produced a new world record for more than a quarter-century. You might say to yourself, “That’s not true—Stephen Tucker killed a world record deer in 2016.” The caveat is that while his deer is the largest whitetail buck shot by a hunter, it’s not the largest whitetail rack in the world, according to Boone and Crockett records. In fact, the average age of the world-record entry for the four whitetail categories—which includes typical and nontypical marks for both whitetail and Coues deer—is 43 years. Any record that lasts multiple generations begs a question: Is it unbreakable? With that in mind, here are 8 other big-game world records that hunters may never beat.

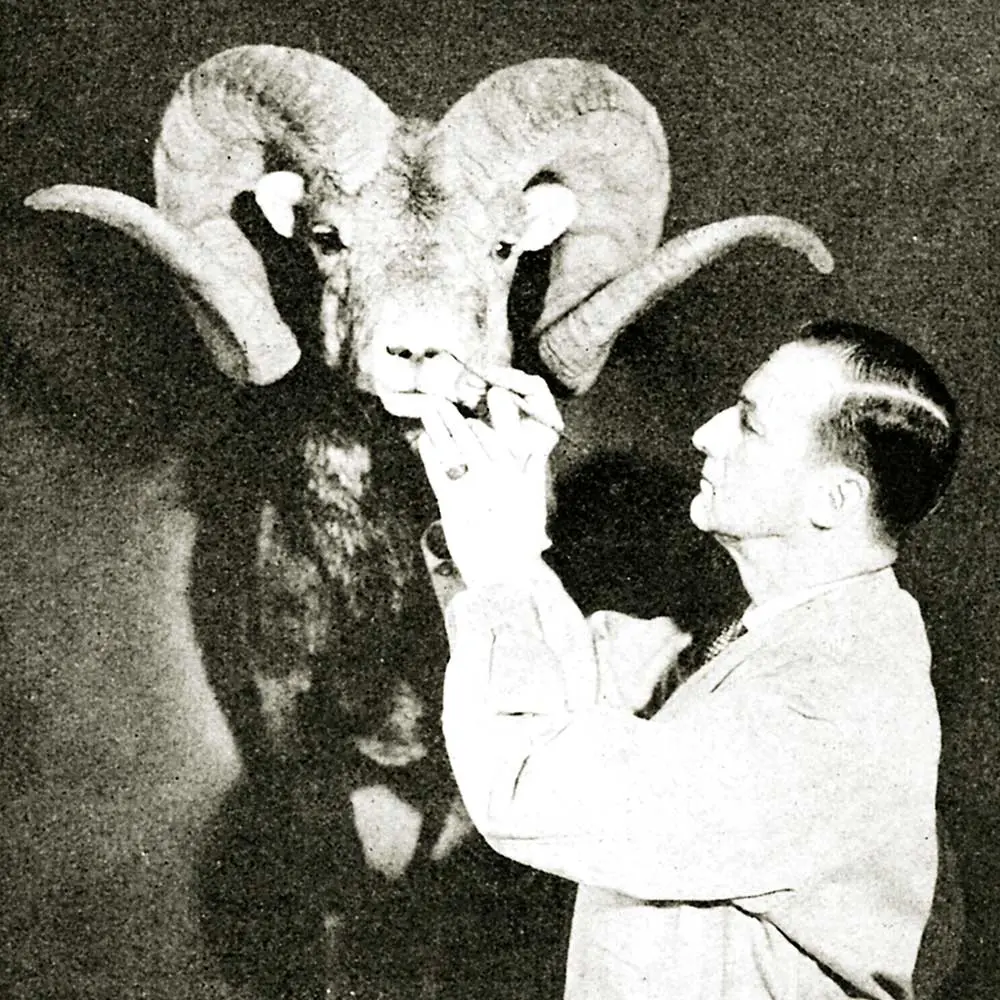

Stone’s Sheep

Chadwick’s ram is the only one in the record books with both horns measuring over 50 inches.

Score: 196 6/8Year: 1936Location: Muskwa River, British ColumbiaHunter: L.S. ChadwickIt has been 82 years since L.S. Chadwick shot what many consider to be North America’s greatest trophy. “They were basically doing a safari into the mountains,” Spring says of the monthlong 1936 expedition in British Columbia’s Muskwa River drainage, “and they came back with a ram that’s still the only sheep trophy in the book that has both horns over 50 inches.” The one other Stone’s ram to score more than 190 was taken in 1962, and since 1970 only three other top-20 rams have been scored. “In modern times, I don’t know if there is a hidden place like the one that allowed the Chadwick ram to get that big,” Spring says. “That one, in my opinion, will be the hardest to top. I think it will stand in perpetuity.”

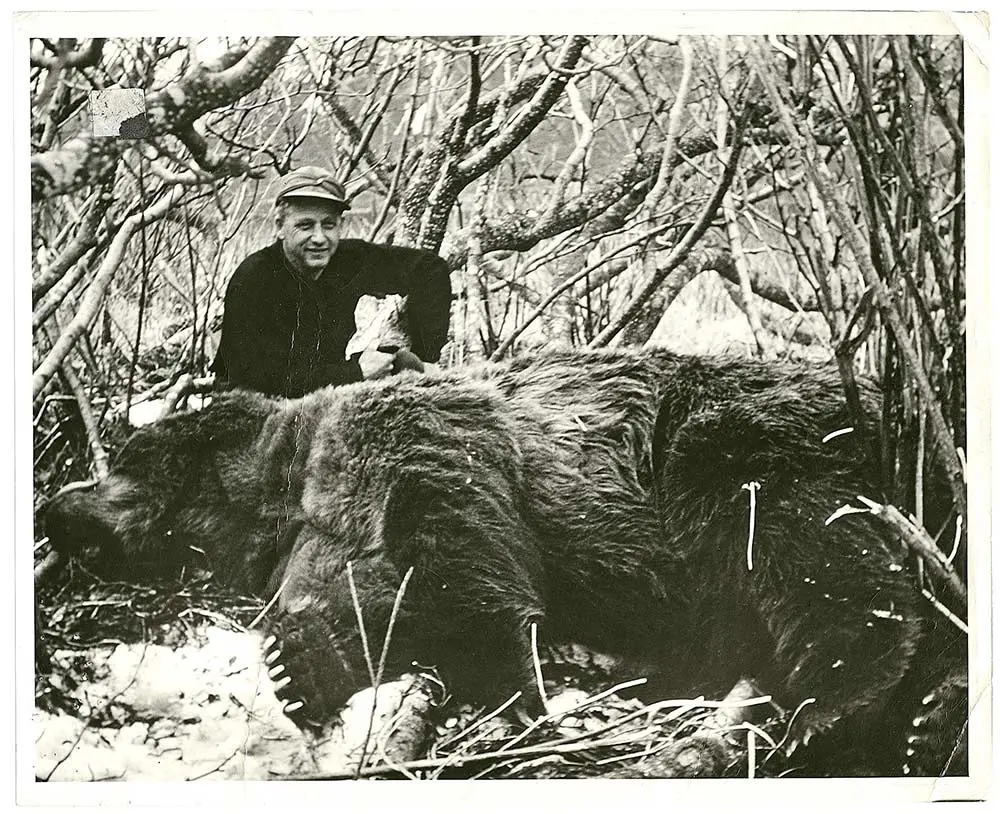

Alaska Brown Bear

Because Alaska brown bears thrive on salmon, which aren’t as plentiful as they were when Roy Lindsley shot his bear in 1952, it may be another 66 years before hunters see another as large.

Score: 30 12/16Year: 1952Location: Kodiak Island, AlaskaHunter: Roy Lindsley“The good old days of the big grizzly are right now,” Spring says—at least north of the 62nd parallel, where range has expanded, overall populations are on the rise, and the number two and number three grizzly bears on the Boone and Crockett list were added in 2013 and 2009. “The Alaska Brown Bear is a different story,” Spring notes. Among the top seven, the most recent harvest date is 1966, and the current world record, taken by Roy Lindsley, has stood since 1952. “Sixty-six years at the top is a very long time,” Spring says, “and considering these coastal behemoths thrive on salmon, and overall salmon abundance in recent years has declined up and down the West Coast, the possibility of this category seeing a new No. 1 anytime soon seems unlikely.”

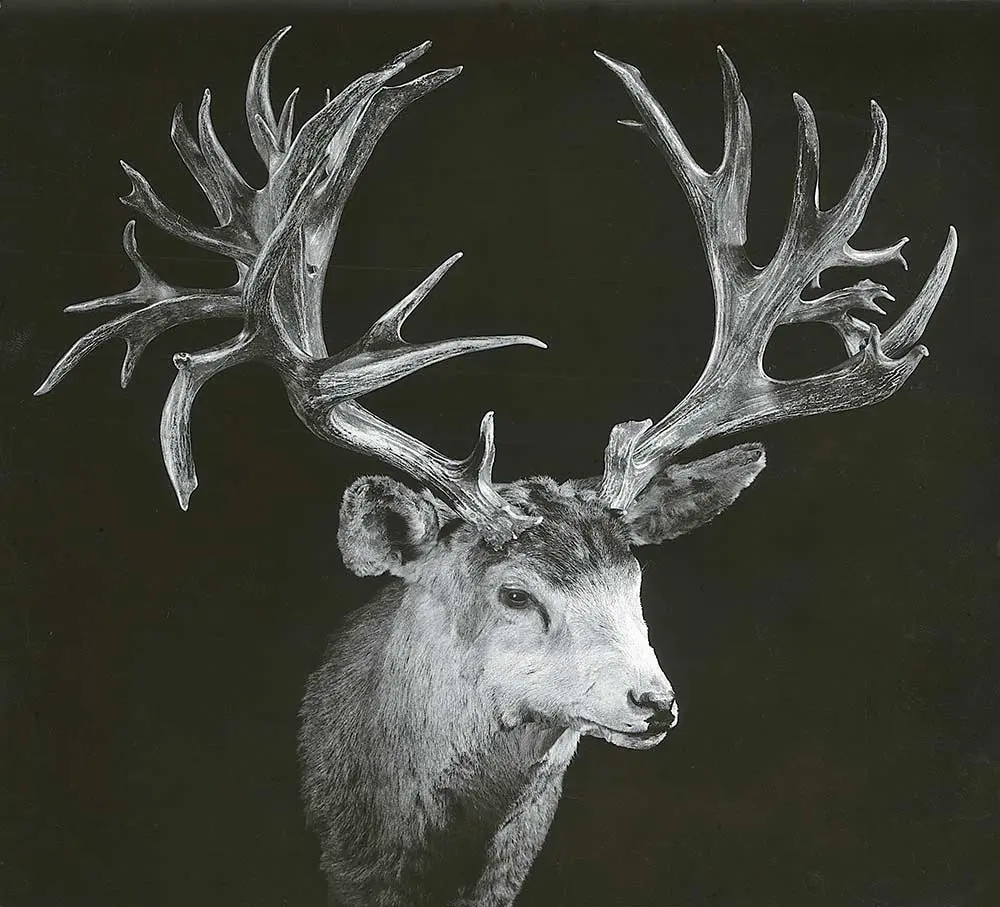

Quebec-Labrador Caribou

Until caribou numbers improve, it’s unlikely a hunter will eclipse Elbow’s record anytime soon.

Score: 474 6/8Year: 1931Location: Nain, Newfoundland and LabradorHunter: Zack Elbow“A few records have been around so long that they look unattainable,” Spring notes. The world-record Quebec-Labrador Caribou, shot in 1931 by Zack Elbow, is exhibit number one. Population numbers have been on a worrying downward trend for all caribou species, and the declines for Quebec-Labrador herds have been so steep that hunting was recently discontinued. “We went from a thousand entries in a three-year period to maybe a hundred,” Spring says, “but we’re starting to see those turn around and come back.” Woodland caribou are currently less numerous overall, but more big bulls are showing up: The same could happen for the Quebec-Labrador caribou as populations recover, but for now this record is etched in stone.

Nontypical Mule Deer

Broder’s record mule deer scores a whopping 16 inches larger than the runner up.

Score: 355 2/8Year: 1926Location: Chip Lake, AlbertaHunter: Ed BroderShot by Ed Broder in 1926, the nontypical world-record mule deer scores 16 inches higher than its closest competitor. Of the top five bucks in the category, only one was taken after 1943: William Murphy’s 325-incher from 1955. That’s a lot of history to overcome, says Spring. “With mule deer, the biggest thing we see is that these older bucks now grow lots of abnormal points as they age. They don’t turn into freaks, they just get kickers and drops and flyers but not enough to ever rival 355.” Combine that with the record’s longevity and the consensus that putting an all-time muley in the books is one of hunting’s toughest tasks, “and it’s a pretty tall order to find that many inches of antler on a mule deer without deductions that would lower the score,” he adds. “Nothing has even come close in nearly a hundred years.”

Typical Mule Deer

Burris Jr.’s buck has a clean, symmetrical size and shape, which doesn’t happen often with old mule deer.

Score: 226 4/8Year: 1972Location: Dolores, ColoradoHunter: Doug Burris Jr.More attainable—but still a long shot, in Spring’s estimation—is the typical mule deer record set by Doug Burris Jr. 46 years ago. The tendency for a buck to experience abnormal antler growth is a factor here too. “What we see in great big, older mule deer is they have a 200-inch frame, but they’ve got 15 inches of abnormal points. They don’t even make the book after deductions,” Spring says. “That’s why the Burris Buck is so impressive. It’s a giant, clean typical, which just doesn’t happen often.” Despite mule deer conservation efforts, overall numbers are down a bit. Blame shrinking habitat and expanding whitetail populations. “Mule deer are an open sage species, and open sage is becoming harder and harder to find,” Spring notes. “In many cases, whitetails are coming into mule deer habitat, and they are just better at utilizing what’s on the land.”

Pacific Walrus

While it’s been some time before hunters could pursue walrus, the Boone and Crockett club does recognize skulls, antlers, and horns that are found and “picked up” because the animal’s size is a reflection of good management and conservation practices.

Score: 147 4/8Year: 1997Location: Bristol Bay, AlaskaHunter: Found and “picked up”Yeah, it’s a technicality, since the Pacific walrus has been sheltered by the Marine Mammals Protection Act since the 1970s. A few coastal dwelling tribes of Alaska Natives (Indians, Aleuts or Eskimos) are allowed to hunt them, but subsistence hunting is usually all about meat, not trophy size. The category’s turnover in 1997 actually makes this the newest world record on this list—but the skull was a “pickup” (in fact, three of the top five on this list are pickups), which the Boone and Crocket Club still recognizes because an animal’s size is often a reflection of conservation efforts and good management. But as hunters, we’re all about harvests, so if you’re curious to see what a world-record Pacific Walrus looks like, stop by Foster’s Bighorn, a restaurant and sports bar in Rio Vista, California. The mount of the former world-record walrus (from 1940 to 1957) and the current number three trophy walrus is part of the famous 250-specimen menagerie that overlooks the bar.

Nontypical Whitetail Deer

How not a single hunter was able to see and harvest the largest nontypical whitetail in the world remains a mystery.

Score: 333 7/8Year: 1981Location: St. Louis County, MissouriHunter: Found and “picked up”The top two nontypicals in the Boone and Crockett books weren’t taken by hunters—a telling detail, Spring believes. “Those are both picked-up trophies,” he says. “So, the question is, do these deer just grow their best antlers at an age when they’re pretty much un-huntable because they are 100 percent nocturnal? Are they there and just not being taken?” Recent kills suggest there’s hope, at least. The Stephen Tucker buck, a 312-inch monster that came out of Tennessee in 2016, ranks third; the 39-point Luke Brewster buck arrowed in Illinois this fall is purportedly in the same ballpark. “Still, adding 20 more inches to reach those top deer seems pretty farfetched,” Spring says.

Typical Whitetail Deer

Thanks to the popularity of sound deer management practices, it may just be a matter of time before a hunter breaks Milo Hanson’s typical whitetail world record.

Score: 213 5/8Year: 1993Location: Biggar, SaskatchewanHunter: Milo Hanson“I’m honestly kind of surprised the typical record hasn’t been broken,” Spring says of the 213-inch 6×6 shot by Milo Hanson in 1993. The Hanson buck “clearly fits our system very well, and there is some credibility to the idea that maybe with some of these records it’s just for our system that they haven’t been broken,” Spring adds. “But the Hanson buck has stood forever: A lot of whitetails have been killed since then, but no one has beaten it.” Given the amount of time, money, research, and technology now invested in growing, scouting and hunting big deer, it may just be a matter of time, Spring says. “I can’t say for sure there’s not one out there on the land. There have been trail camera pictures of deer that I would guess beat the current world record typical, but the thing is, they’re never killed. There’s a video going around right now of a 200-plus typical supposedly in Kentucky—so who knows?”

**Read Next: So You Want to Kill a World-Record Whitetail?

**

Three Big Game World Records Hunters Will Most Likely Top

1. Black Bear

The skull of the world record black bear was picked up in Utah, but a Pennsylvania hunter almost beat the measurement in 2011.

Score: 23 10/16Year: 1975Location: Sanpete County, UtahHunter: Found and “picked up”The current world record for black bear—a 23 10/16-inch skull picked up in Sanpete County, Utah—has stood since 1975, but a Pennsylvania bear shot in 2011 missed the record by only 1/16 of an inch. “The purpose of the Boone and Crockett records is to gauge conservation success and failures,” Spring points out, “and this is one of the categories I am most excited about for the message of solid wildlife conservation it portrays.” States are adding bear seasons and bears are showing up in old ranges where they’ve been AWOL for decades, and the results are evident in the Boone and Crockett entries. More than half of the top 10 black bears have been taken since 2011.

2. Pronghorn

As the pronghorn’s popularity among hunters grew in recent years, so has the number of antelope record submissions.

Score: 96 4/8Year: 2013Location: Socorro County, New MexicoHunter: Mike GalloNewfound respect from hunters is helping drive the pronghorn’s resurgence. Mike Gallo rewrote the top of the record book in 2013 with his 96 4/8-inch buck from Socorro County, New Mexico, and nine of the top 10 records have been taken since 2000, and four of those appeared in the last four years. “There’s more interest in them than there’s been historically,” says Spring, who recalls a time 20 years ago when doe tags came in bundles of five and attitudes ranged from indifference to outright hostility. “When hunters care about animals, they tend to do better, and I think that’s a big reason the top of the pronghorn book has fared so well lately. People have taken an interest in the critter, people are making sure they’re doing well, and people are taking top-end pronghorn.”

3. Alaska Yukon Moose

Hunters have taken other record-sized moose since Rex Nick shot his world record in 2010, so it may be just a matter of time before his record falls.

Score: 266 4/8Year: 2010Location: Lower Yukon River, AlaskaHunter: Rex NickAptly known as the Giant Moose, the largest North American subspecies of moose ranges from Alaska to Western Yukon. The current world record—a 266 4/8-inch bull—was killed by Rex Nick in the Lower Yukon River area of Alaska in 2010. The second largest bull was taken in 2013, and the fourth largest shot in 2017 had paddles that spanned over 80 inches wide and many believed it would overtake the top spot in the books, but the final score fell short after deductions. Hunters killed the ninth and tenth largest in 2012 and 2015. “The trend is looking good,” Spring says.

![Field & Stream [dev]](https://images.ctfassets.net/fbkgl98xrr9f/1GnddAVcyeew2hQvUmrFpw/e4ca91baa53a1ecd66f76b1ef472932b/mob-logo.svg)