_We may earn revenue from the products available on this page and participate in affiliate programs. Learn more ›

_

Everything about modern fly fishing is fast. We’ve got fast rods

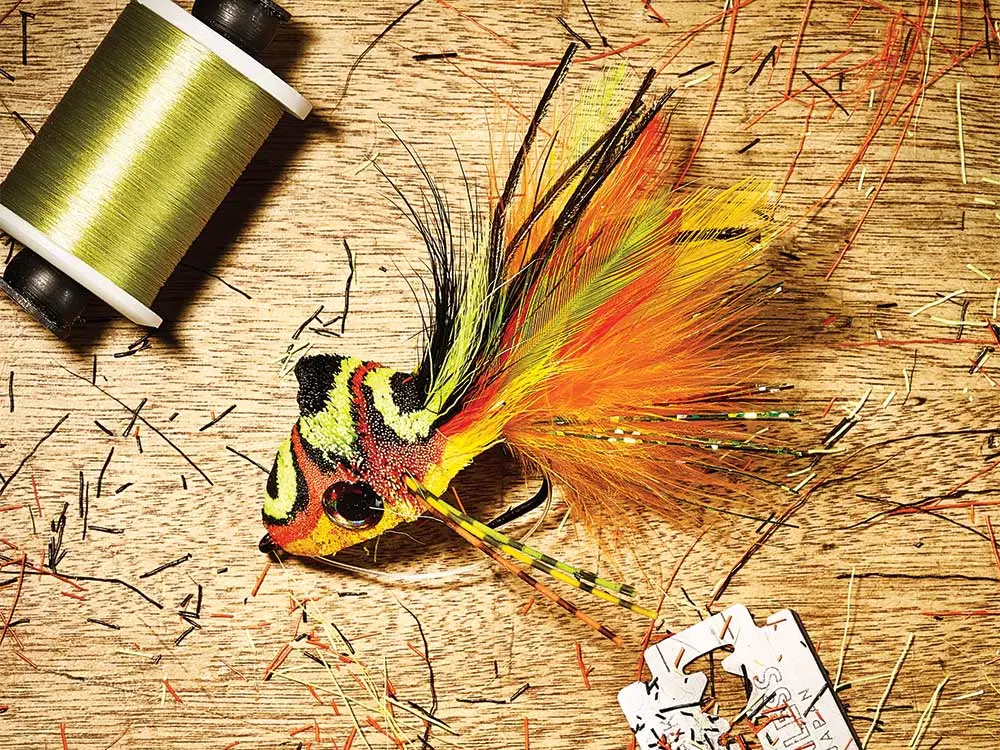

, fast-shooting heads, fast-drying UV resin, and even pre-made wings, legs, and tails that let you whip up flies faster than ever. This might be why spun-hair bass bugs aren’t commonplace in fly boxes today. Everything about them is slow. They need to be fished with patience, you can’t knock them out at the vise, and their air-resistant bodies made Granddad’s slow, noodly fiberglass rod the perfect hair-bug delivery tool. Thing is, spun-hair bugs haven’t lost an ounce of potency since Granddad’s day. And while it’s true that a well-made hair bug isn’t cheap, if you know what to do with one, it’ll repay you with more giant fish.

So, our advice for the new fishing season: Slow down a little, buy or tie yourself some carefully-crafted spun-hair flies, and go coax some topwater strikes with the coolest old-school offerings in anyone’s box. Here’s everything you need to know to get started, including the best deer-hair patters to try, tying tips if you want to make your own, and, maybe most important, how to put these creations to work on the water.

The 4 Best Styles of Hair-Fly Patterns

1) The Classic Popper

A Popper calls in big bass with enticing surface noise. Ralph Smith

Back in the day, spinning hair to create a popper

was practical. In today’s world of myriad prefab foam-popper heads, it may seem outdated. The reality is that in many cases, a hair popper gives you an edge. The difference lies in the sound it makes in the water, which is a much deeper, more “gurgly” one than your average foam popper. Add in hair’s ability to move more water, and you’ve got a hog caller.

2) The Frog

A Frog fly is leathal when worked over the tops of lilies and grass mats. Ralph Smith

Much like a hollow-body plastic frog, there aren’t many places a spun-hair frog

with a weedguard can’t go. You can find hair frogs with popping bodies and diving bodies, but those with more streamlined slider-style bodies are some of the most versatile. They’ll glide over the tops of lilies and grass mats while producing a strong V wake to call in the biggest bass and pike hiding in the salad bar.

3) The Diver

The head design on a Diver allows it to dart a few inches under the surface. Ralph Smith

Designed by renowned angler Larry Dahlberg, the diver’s

magic lies in the head design, which tapers from slanted at the front to a wide, flared collar at the back. Give it a hard strip and it will dive a few inches under the surface, and as water moves over the flared collar, the fly will wobble and shimmy seductively. Strip slowly and a diver will get smoked as it wakes and gurgles across the surface.

4) The Mouse

Monster brown trout have been know to slam Mouse flies after hours. Ralph Smith

Even a small bass can easily suck down a hefty hair mouse

. If late-night brown trout hunting is your game, however, you only tie one of these bushy fur balls on when you’re after “the one.” It takes a big mouth and strong commitment for a trout to eat a hair mouse, but when it happens, make sure you feel your line tighten before you set. Otherwise, you’re just going to yank the midnight snack away from the fish.

Fly-Tying Tips for Hair Bugs

A spun-hair bass fly gets a trim. Ralph Smith

Pat Cohen of Super Fly is the modern-day hair master. So exceptional is his work that many of his fans consider his flies more art than tackle. It’s no secret that making quality hair bugs is meticulous work that takes plenty of practice to perfect, but if you’re thinking about giving it a shot, Cohen says understanding these three hair-spinning rules is critical before you get started.

1) Deer Belly Hair Beats Tail Hair

“I think a lot of people mistake bass bugs as being made of bucktail,” Cohen says. “Bucktail doesn’t flare properly. I also see a lot of folks trying to use deer body hair, but it’s soft and absorbs a lot of water. The flies don’t always float correctly and often flip over on their backs. To make a good bass bug, you always want to use quality deer belly hair. It’s stiff, flares correctly, and has the most buoyancy.”

2) Tie Them Tight

“One of the biggest issues tiers have is thread control,” says Cohen. “When it’s time to cinch a stack of hair in place, people are afraid to put too much tension on the thread because they don’t want to break it. But you have to break thread now and again to learn how much tension you can put on it. If you don’t use enough tension, your fly will weaken and fall apart after a while. I use gel-spun threads for all my bugs because they can handle a lot of tension.”

3) Keep the Body Shapes Simple

“Carving bass bugs takes a lot of patience,” Cohen says. “When you’re ready for shaping, the trick is not thinking of the final shape. You want to envision a body in its most basic form. As an example, if you break down a popper to its basic fundamental shape, it’s a rectangle on a hook. Trimming the hair into an even rectangle is easier for people to do. Once you have that shape completed, then you can go back and round it into the popper you want.”

Three Tactics for Fishing Deer-Hair Flies

Big largemouths have a hard time resisting the unique gurgle of a spun-hair bug. Tosh Brown

1) Get Your Bugs Riding Low

Not only is Pat Cohen the man when it comes to tying hair bugs, he’s also a leading expert on fishing them. It’s important to remember that a hair bug behaves differently than a similar fly with a foam, cork, or balsa body, which is why Cohen says you don’t want to just tie one on and slap it down. A little bit of hair-bug prep goes a long way.

“I prefer to fish hair bugs that are waterlogged,” Cohen says. “I’ll actually soak them for up to an hour before fishing to make sure all of that hair absorbs as much water as possible. Just before I start casting, I’ll squeeze the bug out. What you end up with is a fly that will naturally ride lower in the surface film.”

According to Cohen, a hair bug that’s riding low produces a deeper gurgle and pop that simply can’t be matched by topwater flies with solid bodies. This sound can be a dinner bell for huge bass if you present the fly correctly. Cohen says it’s important not to overwork a topwater hair bug. He always lets the splat-down rings dissipate before moving his fly. “I give it a couple of pops and let it sit for three to five seconds,” he says. “If there’s a bass in the area, it knows your fly is there. Bass are naturally curious and will come scope it out. You just have to vary your retrieve cadence and speed to figure out how to make it eat.”

2) Best Fly Lines for Hair Bugs

Hair bugs are surface flies, so you’d naturally want to cast them on a floating fly line. Most of the time, anyway. If you’re looking for a leg up on trophy pike, bass, or even trout, Cohen recommends ditching the floater, particularly when you’re using a hair diver. Pair these buoyant bugs with a heavy-grain sink tip, and the results can be positively stunning.

“That sinking fly line wants to go down, and a floating fly wants to come up,” Cohen says. “So you get this up-and-down jigging action, along with this really crazy, erratic side-to-side motion. It’s almost similar to a crankbait’s wobble. You can fish it just like a streamer, and it’s absolutely deadly.”

To dial in exactly the action you want, Cohen says, all you have to do is play with leader length. The longer the leader, the more time it will take the sink tip to pull the fly down and the more subtle the action. If you use a short 2- or 3-foot leader, the fly will drop faster and you’ll get increased action on the strip. By varying sink-tip weight and length, you can also fine-tune exactly where in the water column you want that diver to work or suspend.

3) Add a Dropper to Your Popper

Deer-hair poppers might have the uncanny ability to draw in bass, but that doesn’t always mean those bass are going to commit. This is one of the reasons why Cohen often hangs a dropper under his flies. He says the method makes the play more often than not when bass are being finicky.

“What I do is take a 24-inch piece of leader material and tie it to the bend of my popper hook,” Cohen says. “Then you tie a small sinking fly to that leader. A little Clouser Minnow is one of my favorites. As you work that popper, that Clouser is bouncing around below it, and it looks just like an injured baitfish. So you’ve got the unique sound of the popper to call the fish in, but also a smaller target if a bass won’t hit the bigger meal.”

If you tie up Cohen’s “popper-dropper” rig, just don’t forget to alter your casting a bit; fail to open up your loop, and that little Clouser can create some gnarly tangles or end up in the back of your skull.

![Field & Stream [dev]](https://images.ctfassets.net/fbkgl98xrr9f/1GnddAVcyeew2hQvUmrFpw/e4ca91baa53a1ecd66f76b1ef472932b/mob-logo.svg)